There continued to be a buoyant mood in markets in Q4 – helped by the positive clinical results, and subsequent approval, of several vaccines for COVID-19. This was despite many northern hemisphere countries facing substantial “second waves” of infections.

Following the announcement of the Pfizer vaccine trials on 9th November many companies perceived to be most impacted by the pandemic saw large share price gains. By way of example one of our portfolio companies, Host Hotels, saw its share price increase by 30% in a single day. I believe that the link between company share prices and their underlying business conditions is often “fuzzy”, and market moves such as this only serve to reinforce this belief. Whilst the vaccine news is undoubtedly positive, for many such companies I thought the size of the reaction was disproportionate. It felt that many market participants were rushing “from one side of the boat to the other” to buy up companies that would benefit from a return to normality.

Observing markets in the last year has, more generally, served to strengthen my belief that short-term price movements are dominated by emotion more than detailed analysis. It has felt that the link between “Wall Street” and “Main Street” has become particularly stretched (not that the history books suggest they have ever moved in lockstep).

My conviction that there is a risk of an asset price bubble has strengthened over the last three months. I believe that this bubble is particularly focused in the US on companies that are perceived to be “high growth” or have dominant technology franchises.

What is the case for us witnessing a bubble?

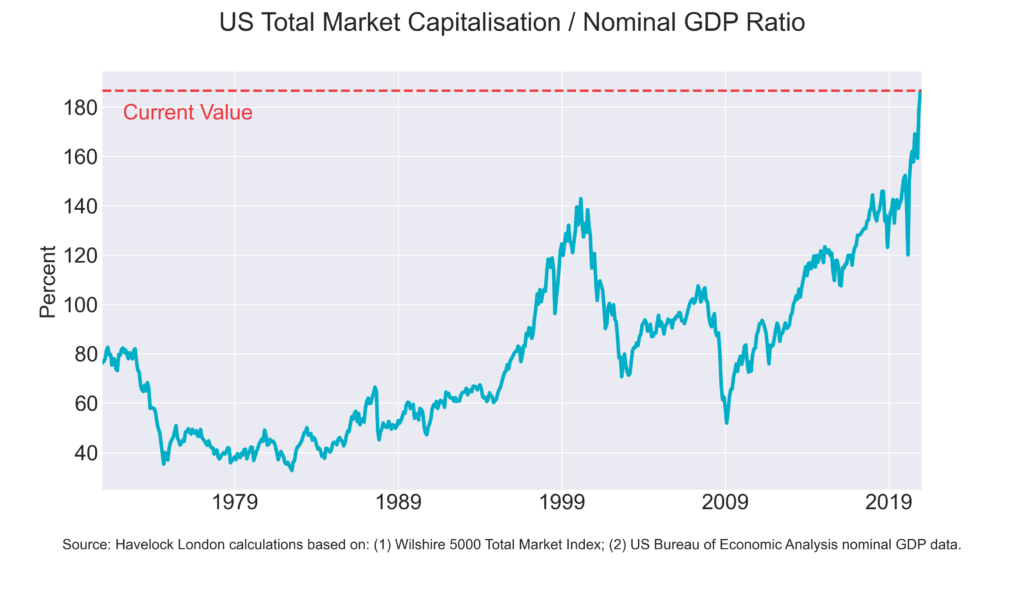

- The total value of all public US companies relative to US GDP is “off the charts” with a ratio of 1.9x. During the “dot com bubble” this ratio peaked at 1.4x[1]. This is a metric favoured by the famed investor, Warren Buffett, and is at the highest it has been in 50 years. The extent to which this ratio has “spiked” in the last two years gives me cause for concern.

- There has been a frenzy of companies raising capital on the public markets. Much of this activity has been via “Special Purpose Acquisition Companies” (SPACs) – which are a way of raising money from investors with less scrutiny than a traditional Initial Public Offering (IPO). It is the first year in history that US companies have raised more than $100Bn in IPOs, with more companies having been made public than at any point in the last 20 years.[1]

- From a “bottom-up” vantage point the valuation of companies such as Tesla or Nikola look, to my eyes, hard to justify. The ascent in Tesla’s share price has been so rapid that it appears, to me, to have the hallmarks of a speculative mania. The company has a market share of global car sales of circa 0.7%, but it is now worth more than the combined value of its eight largest competitors[2]. For a discussion of Nikola see my last quarterly letter.

- There exists a compelling “this time it is different” story. The cornerstone of this is low interest rates and very “accommodative” monetary policy, that pushes investors to justify paying higher prices for assets in the search for yield. There appears to be an acceptance that interest rates will be low for a long time into the future, that Central Banks will support asset prices and that this can be achieved without any other adverse economic consequences.

- There appears to be a growing public euphoria for share trading. Google Trends data[3] for North America shows that google searches for “share” during 2020 have been higher than at any point since 2004 when the data begins. Bubbles are always accompanied by stories of making “easy money” that stoke up a “fear of missing out”. I believe that podcasts, YouTube channels and such like are providing the means to disseminate these stories and encourage retail speculators.

- Whilst more difficult to quantify, it appears that sentiment in the markets is not being impacted by bad news in the way that might be expected. A bad unemployment number or surge in virus cases seems to be taken as a sign that there will be more stimulus – which will be good for markets. By the opposite token good news that is positive for the economy is also taken as good for markets. I do not see how this can continue and am concerned that many investors are being lulled into a false sense of security by the “heads I win, tails you lose” environment.

What about the opposing view?

For each of my points above there is an opposing view.

- There is no fixed law governing the overall size of the US stock market relative to the general economy.

- The frenzy of IPOs could be rationalised by the continued move to a digital economy creating many new worthwhile investment opportunities.

- Companies, such as Tesla, could be argued to have such strong technological advantages that they offer sufficiently high long term future growth to justify their current valuations.

- Low interest rates could remain for many years and, despite the massive monetary expansion, may be accompanied by economic stability – for reasons that may not be obvious.

- The public enthusiasm for stock markets could turn out to be not such a big deal, or perhaps a rational consequence of more individual pension saving or even a lack of any other worthwhile investment options in their view.

- We could be at the cusp of a continued disruptive technological revolution, meaning that the prospects for the future are great irrespective of the minutiae of 2020.

I think it will be clear which side of the debate I lean towards. When I look at the evidence collectively, I believe that there is a real risk that we are seeing a bubble in some asset prices.

What are you going to do about it?

Our approach to protecting our client’s money from this threat is two-fold:

- We look to own relatively lowly-leveraged public companies, where valuations do not rely on an undue level of optimism. Our approach keeps us away from owning companies where high valuations can only be justified by forecasts of their businesses seeing high growth for a long time into the future.

- We currently hold a fraction of the fund in cash, both as a form of risk control, limiting the fund’s exposure to falling equity prices, and a source of dry powder that can be quickly deployed when risk aversion increases in markets.

It is my belief that forcing yourself to be fully invested in equities is like tying one hand behind your back when it comes to managing the risk of financial loss. It means that your risk of losing money is entirely determined by your choice of investments, without any other way to make this risk stable through time. We believe that if our risk of financial loss is consistent through time it will in turn help increase our long-term compound return.

Our investment mantra is that we wish to own a portfolio that will be robust in a range of scenarios. This is because there are many factors in financial markets that we cannot realistically expect to forecast. This balanced approach has served us well since we launched the fund, but risks making us, at times, look needlessly cautious. In the scenario that financial markets are not adequately reflecting the economic impact of the pandemic, I think this caution will be justified.

Despite my concerns of an asset price bubble, I see evidence that there are many companies that do not require optimistic forecasts to justify their current prices. Increases in market prices have not been unilateral for all companies. For this reason, I believe that a valuation focused approach to investing offers both an opportunity for profits and a way of side-stepping the most egregious speculative excess.

[1] https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/newsroom/2020/12/ipo-report-2020

[2] https://wolfstreet.com/2021/01/02/tesla-finally-almost-hit-500000-deliveries-2-years-behind-its-2016-promise-for-a-global-market-share-of-0-7/

[3] https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=US&q=shares