In response to the global pandemic central banks and governments have delivered record amounts of economic stimulus. Much of this has taken the form of increasing money supply via buying financial assets, following which asset prices look high relative to their history.

As observed by famed investor Howard Marks, a world with high asset prices is a world of low future returns. This is most easily understood by a traditional bond investment that pays a fixed coupon; higher prices clearly equate to lower income yields. The same argument applies elsewhere when asset prices increase by more than their underlying economics or earning power.

What we do not know is if asset prices are now at a permanently higher plateau, and lower investment returns are the new norm, or if we are witnessing a spectacular “everything bubble” that will create financial pain when prices “normalise”.

Where does this leave investors?

The easiest response is to do nothing and knowingly, or otherwise, accept that future returns will be lower. I believe this is the path of least resistance, and thus the one that most investors will take.

To try and avoid lower future returns, I see only three credible options:

- Take less risk in the hope that asset prices are cheaper in the future.

- Take more risk in the hope that the status quo holds, and you earn a higher return.

- Try to do something “clever” to make a higher return with no additional risk.

Doing Nothing

In investing, doing nothing, is often a good strategy. It allows you to side-step the latest fads, avoid acting on emotions and helps ensure that returns are not eaten up by transactions costs.

In the last decade I believe many investors have navigated towards owning a portfolio dominated by “growth” stocks and government bonds. These have both been the “gifts that keep giving”, however I believe they are destined to produce lower returns in the future.

In the case of government bonds, and fixed income investments more generally, we have experienced 40 years of falling interest rates. This provided a tail wind that helped increase bond prices (since they move inversely to interest rates). In the last decade UK 10-year Gilt yields have fallen from around 3% to 0.5%. I calculate that for investors to receive a similar return in the next decade, as in the last, 10-year UK interest rates would have to fall from 0.5% to around -4%. I think this is possible, but unlikely.

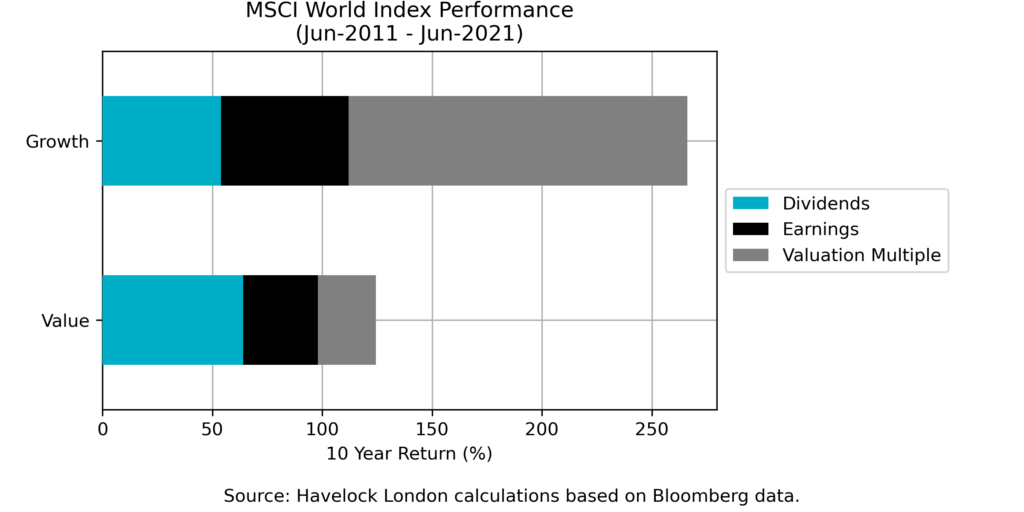

So called “growth” stocks have also benefited from a tail wind in the last decade, with their prices moving to be much higher multiples of their underlying earnings. The price to average 10-year earnings ratio for the MSCI world growth index almost doubled in the last decade, moving from 25x in June 2011 to 48x in June 2021. I do not think that such a doubling is likely to happen again in the coming decade.

The chart above is an updated version of our analysis from my September 2020 quarterly letter and shows our estimate of the performance drivers of the MSCI world growth and value indices in the last 10 years. This makes clear the impact that earnings-multiple expansion has had on the performance of “growth” stocks.

Taking less risk

Taking less risk is most easily achieved by holding more cash or other short-dated “safe” investments. If asset prices fall, then you can swoop in and buy at prices lower than today, locking in a higher return. If asset prices do not fall then, you will clearly have forgone the returns that holding “riskier” assets would have provided.

I suspect that some investors will proceed on a “do nothing” basis, expecting that they can quickly switch to a “take less risk” strategy as and when they think asset prices are falling. This strategy sounds appealing but is hard to achieve as major turning points in markets are rarely well signposted.

Taking more risk

Taking more risk is most easily understood in fixed income markets, where the interest rate you earn is set according to the perceived risk of the borrower not meeting their payment obligations. Orthodox theory in financial markets builds on this to say that more generally the rate of return you earn is dictated by the risk you are willing to take.

One clear mechanism for the risk/return trade off in equity markets is that when a company increases its leverage via borrowings it increases the upside for shareholders, but also the probability of them being “wiped out” if there is a bump in the road.

Doing something “clever”

What most investors would ideally like, is to find a way of side-stepping the orthodox relationship between risk and returns, to make a higher return without a corresponding increase in risk. The financial services industry is always keen to meet this desire and so there is never any shortage of products making such claims.

Given that there is no unique way to define risk it is often the case that doing something “clever” will result in swapping one risk for another. For example, the private equity industry touts the prospect of higher returns than public equity markets, but it comes with the risks of lower liquidity and higher leverage.

I am front of the scepticism queue when it comes to “clever” financial products. However, I believe that owning “high quality value” stocks is currently presenting investors with an opportunity to earn higher future returns with less risk.

I see evidence of this from a “top-down” perspective because as shown above “value” stocks have not experienced the earnings-multiple expansion of “growth” stocks, and so I see them at less risk of a corresponding multiples contraction. More importantly I continue to see evidence from a “bottom-up” view, where our research leads us to companies that we judge as high quality, having longevity of earnings power and being available to purchase at a more reasonable price than many more popularly owned companies.

Put differently, I believe that in the current market environment there is still merit to being selective about which companies you own. Whilst, equity prices are high on average, I believe that their increase relative to underlying earnings has been concentrated far more in some corners of the markets than others. Relative to many other “clever” investment products on offer, I find the argument for a “value” strategy to be reassuringly straightforward.

Investing in a low return world.

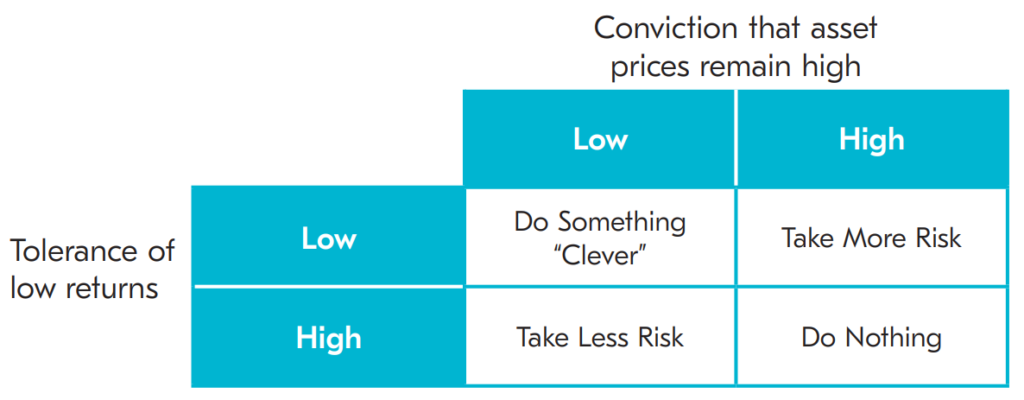

The above reasoning leads to my mental model for investing in a low return world, that I set out in the 2-by-2 matrix below.

I have mapped the four possible actions for investors to two simple questions about their outlook. The strength of an investor’s convictions in the above two questions should dictate their behaviour. Very few investors, myself included, will hold convictions so strong that they pursue only one of these four options to the exclusion of the others.

At Havelock, we have relatively low conviction that asset prices will remain permanently high and a low but not at-all-costs tolerance of low returns. This means that our approach should be skewed towards the top-left part of this matrix if we hope to achieve our goals.

The cornerstone of our approach is to hold assets that we think are reasonably priced and do not require too much optimism about the future. This requires us to understand and value each business we invest in, and I put this in the “doing something clever” category. We do assume general equity market risk and allow ourselves to hold some cash “dry powder”, so there are also elements of “do nothing” and “take less risk” in our approach. More specifically we attempt to limit the losses we will make during a large fall in general equity markets to be less than most broad market indices.

Why am I telling you all this? I believe successful investors find ways of reducing the complexity of markets to allow logical reasoning about where they think they are and where they want to be. There is no unique way to do this, but I thought I would lay out my stall for how I think about the challenges of investing in a low return world.