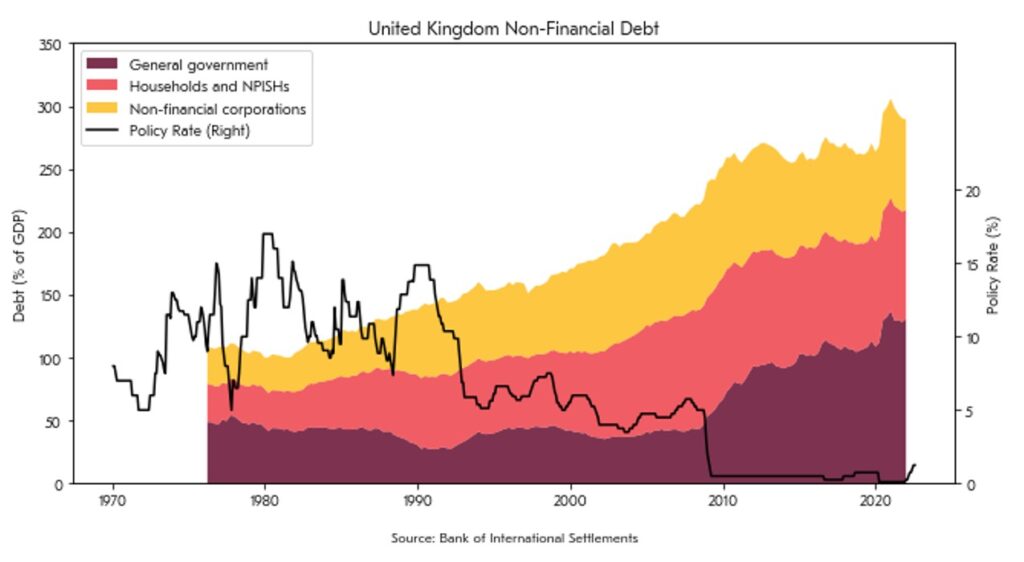

As a nation the British like to borrow. In the thirty years prior to 2008, companies and households steadily took on more debt, punctuated by a “credit crisis” that called into question the ability for it to be repaid. Since then, and despite “austerity” measures, the baton passed to the Government. The result is that total borrowing in the UK, excluding financial institutions, has been on a steady rise for 40 years – moving from around one times GDP to almost three.

Alongside this increase in debt, interest rates have fallen, such that we have not actually had to spend more to service the enlarged debt. This, of course, is because the Bank of England has justified low interest rates as a response to low levels of price inflation.

That brings us to the present day. The recent jump in inflation means it has reached levels not seen since the 1970s, leading many commentators to draw a comparison to these times. Stories of strike activity and wage disputes, together with an energy price shock, further justify the comparison. Where the comparison falls short, is with respect to both the amount of debt in the economy and the level of interest rates. This is made clear in the chart below:

With total debt in the UK of three times GDP, a 1% increase in interest rates would require an additional 3% of GDP to be spent on interest payments. Through this multiplier effect, a quite plausible scenario of a 3% rate rise would require an additional 9% of GDP to be spent servicing debts. Clearly it would need a high level of underlying growth to both cover such an additional cost and see overall GDP growth. This is a very different situation to the 1970s.

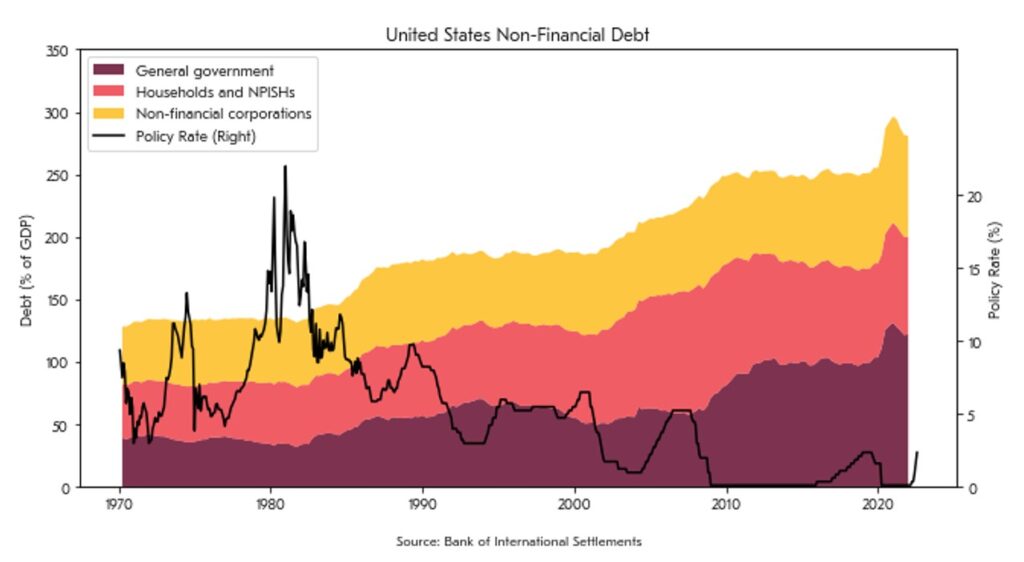

Although this narrative creates an uncomfortable picture for the UK, it is almost identical to the US, where debt accumulation has followed a strikingly similar path. It follows that the build-up of debt in the UK economy does not, on its own, justify this year’s large fall in the value of the Pound against the US Dollar. Clearly the risk that this debt impacts future economic growth is much the same in both countries.

We do not make investment decisions based on macro-economic forecasts and so what is my interest in this data? It is because we want to own a portfolio that is robust to what the future could reasonably hold, and these insights makes me cautious about extrapolating recent experience. We want to allow for the risk that the investing climate moves into a new and unfamiliar paradigm. Could this be the end of a debt “super-cycle”, the eponymous Minsky[1] moment?

Based on the shadow that debt now casts over the world’s major economies, low interest rates and increased amounts of leverage have not only benefited corporate profit margins but have also supported high asset prices. With all else being equal, higher interest rates will put this into reverse. This comes at a time when profit margins are already under pressure from high commodity prices, rising wage pressure and a less friendly global stage for doing business.

Specific to the UK, this year’s circa 15% fall in the Pound against the US Dollar has shielded many investors from the full force of asset price falls abroad. This comes on the heels of a prolonged period of strong performance for US equity markets. I am under no illusions that the UK faces challenges ahead, but I believe that it is not alone in this regard. There is a risk that as attention moves to problems elsewhere in the World, a reversal of the exchange rate and premium on US equity markets will create a headwind for many investors.

Despite these concerns I see reasons for optimism, as I believe the current environment is creating opportunities for discerning investors. Based on valuations, among other observations, I believe that there is a lot of herd behaviour in markets – investors moving their capital based more on emotions than analytical insights. We see examples of companies with valuations close to 40-year lows, where we believe the challenges they face have had an exaggerated impact on prices, as investors “run scared” at the slightest sign of bad news.

Clearly, I do not know what the next chapter of this story will look like. However, as students of market history, I know that knowledge of the past can only make whatever happens next seem less surprising!