The world appears to be at something of a crossroads, with investors divided as to if last year was a temporary setback for markets, or if we have moved into a new paradigm. I do not know what the future holds but, after a decade of “free money” interest rate policies, believe investors face a lopsided outlook.

What do I mean by lopsided? There are several ways in which our global economic system looks extreme relative to history, and I think it more likely that these reverse, than they continue. My views are based on a simple “trees don’t grow to the sky” logic, and in what follows I set out the three major sources of asymmetric risk that I see.

Debt

The high level of debt that has been built up in the last two decades is the first risk I see. It means that we have collectively all consumed more than we earnt, which generated extra demand for goods and services. I think it more likely that this trend reverses, than continues, which would result in reduced consumption. This would clearly be bad news for corporate profits and bad news for investors.

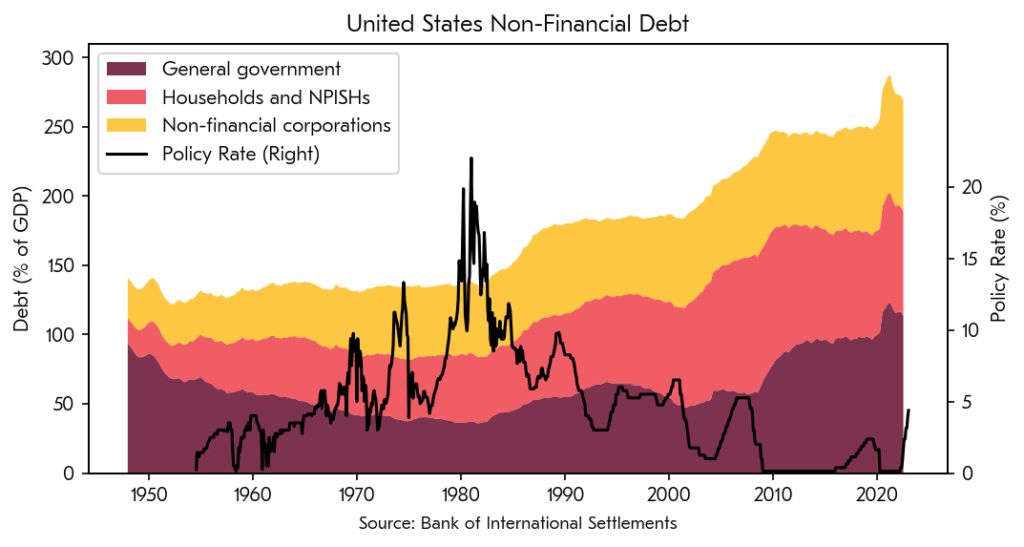

The chart below shows the total amount of debt in the US economy, expressed as a percentage of GDP, and split between government, individuals, and companies. The US is not alone in having a post-war record level of debt, with most mature economies having followed similar paths. This build-up reached a crunch point in 2008, since when the “can” was kicked down the road by governments increasing their borrowings to shore up their economies.

The increase in debt since the 2008 financial crisis was helped by the world’s major central banks increasing the supply of money – in layman’s terms “printing” it. This newly created money flowed to borrowers, via the workings of the banking system, and low interest rates kept the cost of this debt manageable. These low rates effectively meant that “free money” was given out, much of which was used to buy existing financial assets. Some of it flowed to new entrepreneurial endeavours, many of which perhaps would not be viable in the absence of free money. This became known as the “everything rally” since every investment imaginable appeared to only ever go up.

I think it fair to describe this as “unprecedented” – certainly nothing like this has happened within living memory. It seems more likely, to me, that we now see debt levels fall, rather than rise to ever more extreme levels. If this does happen, we will all be consuming less, as more money flows to repay debts rather than buy new stuff. It will also mean less competition to own assets which, with all else being equal, will make them cheaper. Finally, the least viable enterprises will not survive without free money, and so they will fail, which will make investors more fearful of losing their shirt.

Inflation

The risk of higher for longer inflation is the second threat I see. I think this because of the possibility that historic structural deflationary forces fall away, revealing the consequences of zero interest rate policies. This would be bad news for investors, both because higher costs squeeze profit margins and because it erodes the purchasing power of savings.

Central banks oversaw an increase in debt because their mandate was to manage inflation, and whilst it was low, they were single minded in trying to make it higher. They wanted to do this by getting us to all spend more. Their actions were based on the economic theory that they can control the “temperature” of the economy by altering the supply of money – the ideal being steady economic growth, a low level of unemployment, and a modest level of inflation.

This economic orthodoxy meant that the tidal wave like force of mobilising the Chinese population into the global workforce was somewhat ignored. Since the actions of central bankers appeared to create little risk of run-away inflation, creating new money started to look consequence free. This spawned the “Modern Monetary Theory”, that we can print money, grow governments debts, and there will be no nasty consequences.

There are many historical examples of how enthusiastically printing new money led to high inflation, such as the story of Scotsman John Law[1] and the French monarchy. I think it is too soon to know that the recent bout of inflation is under control, not least because I think that factors like wage negotiations or debt refinancing introduce significant lags in the way the economy responds to changed conditions. By contrast the commentary in financial markets seems to assume a near instantaneous transmission of central banks actions into every corner of the economy.

The deflationary impact of moving manufacturing to lower cost countries should be expected to diminish, as we run out of things to offshore. On top of this aging populations in mature economies will mean fewer workers, who in turn demand higher wages that add to inflationary pressures. We are already seeing signs of the baby boom generation prioritising a gentile retirement over working.

Cynically, high inflation will also offer governments an easy way out of their large debt burdens, by repaying lenders with “debased” currency. Allowing inflation to run above the much-heralded target of 2%, would be a form of hidden taxation that is more palatable than the alternative of direct tax hikes.

Profit Margins

The risk of falling profit margins is the third threat I see. I think this because they look high relative to history, and the higher they are the more difficult it is for them to further increase. This would be bad news for investors because falling corporate profits would both reduce dividends and probably also equity market valuations, lowering the returns from owning stocks.

The economic environment of recent history provided companies with low borrowing costs, low taxes, and opportunities to grow margins by offshoring. Against this backdrop corporate profit margins have been running at post-war highs.

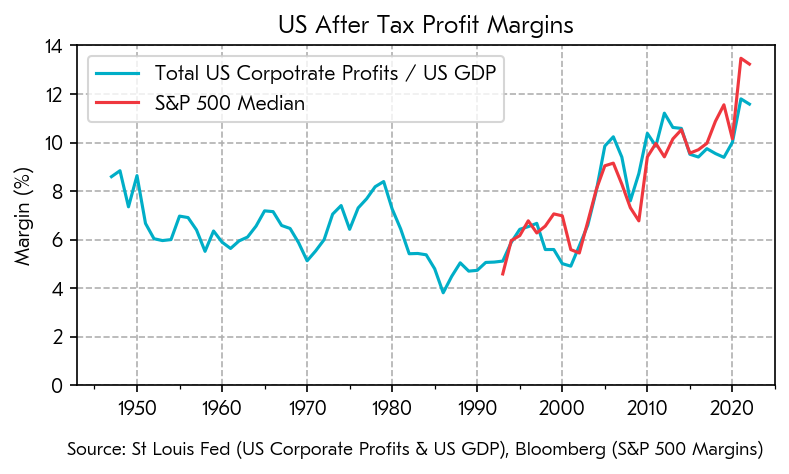

The chart below shows the history of after-tax profit margins in the US. The long-term data in blue is the total corporate profits reported to US tax authorities as a percentage of GDP, whereas the more recent data in red is based on the margins of individual S&P 500 companies.

The chart demonstrates how corporate profit margins have been drifting higher for the last two decades and appear to have had a particular boost in the last couple of years. I have shown data for the US, but other regions have generally seen the same trend, albeit with less extreme increases.

Part of the rise in profit margins appears to have come from a shift towards asset owners receiving more of the spoils of capitalism than workers. This has partly played out via lower corporate taxes, meaning that Governments have been less able to keep pay in the burgeoning public sector in line with inflation. A shrinking workforce and high levels of employment may tip the balance of power back towards employees, with the current strikes in the UK making this seem like a very real prospect.

Current expectations among investors seem anchored on profit margins continuing at levels that look extreme versus history. There is no reason that this can’t happen, but it is clearly not a given.

Conclusion

We do not make investment decisions based on macro-economic forecasts, because I have no reason to think that we can do so successfully. We do, however, want to own a portfolio of companies that will be robust to whatever the future might hold, which means that we spend time thinking about how different economic threats would impact them. We want a “margin of safety” in our investment decisions, such that they are not made based on the assumptions that the favourable conditions of recent history are a given.

Before you start stuffing gold bars under your mattress, what I see are threats, not certainties. There are reasonable counterarguments for why the status quo might continue. For example, automation might offset the impact of an ageing workforce and support higher profit margins, or the rise of India could follow in the footsteps of China to the benefit of the world economy. Perhaps we can fund government spending by printing new money, with no ill effects?

My message is that there are several important ways in which the current economic environment looks extreme relative to history, and so I think investors face a lopsided future with a greater chance of a tough road ahead than a favourable one. Although I think the future is mostly unknowable, I believe it is possible to reason about what is more likely based on an understanding of history.

The “playbook” that has worked so well for investors in recent years will work less well in a world of higher interest rates, higher inflation, and lower profit margins. In the extreme it may not work at all. Optimistically a move towards this new paradigm might create opportunities for thoughtful investors. In a world where “everything” doesn’t always go up, I believe that focusing on the fundamental value of what you own offers the best chance of a favourable outcome.

What have we learnt from history? In the words of Warren Buffet:

“What we learn from history is that people don’t learn from history.”