As professional investors, managing the risk of losing money is a responsibility we take very seriously. The traditional approach when managing a portfolio is to allocate money to different opportunities as if it were a pie being sliced, with each slice being measured by the amount of money invested. Limiting how big a slice of pie you eat is a good way of managing the risk of over-eating, but when it comes to investing, judging risk based on the size of an investment works less well.

The same amount of money invested in two different companies does not result in the same risk of loss. For example, the amount of debt a company uses will alter the chances of it exposing investors to future losses. It is for this reason that we spend time looking inside the pie (company!) to understand the threats to a company’s on-going health.

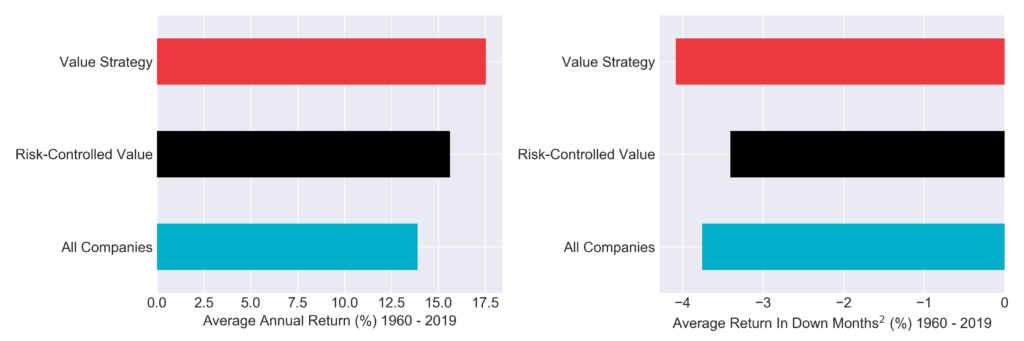

Our investment approach does not require us to be fully invested in stocks at all times, and the analysis below demonstrates how this helps us manage risk. We show the performance of a naïve value strategy, which each year selected the cheapest 10% of US companies based on their price/earnings ratio. This is compared to the performance of having invested equally in all US companies[1]. These results support the established academic result that a valuation-driven strategy can deliver superior long-term returns. As a simple measure of risk, we show the average return in down months[2], and on this basis the simple value strategy exposed investors to a greater risk of short-term loss than investing in all companies.

The value strategy also had long periods of time when it was subject to above-average levels of volatility as measured with the “beta” statistic (which quantifies the volatility of a stock, or group of stocks, relative to the average). If we relax the need to invest entirely in stocks, we can attempt to make this risk more consistent through time. The “risk-controlled value” series in the charts takes the simple value strategy and attempts to control its relative volatility (or beta) to be 90% of the average. It did this by varying its allocation to the “value” stocks and investing the spare cash in US government bills. This combined approach of a value strategy coupled with risk control delivered simulated returns that were above average, whilst reducing the typical monthly losses.

This exercise is just an illustration and does not represent the actual way in which we select and weight companies in our portfolio. Instead, we wish to demonstrate that forcing yourself to be fully-invested in equities is like tying one hand behind your back when it comes to managing the risk of financial loss. It means that your risk of losing money is entirely determined by your choice of stocks, without any other way to make this risk stable through time. Being able to hold some money in the safe harbour of government debt can provide greater freedom to actively control this risk, whilst seeking the best long-term investment opportunities.

Using this flexibility to pursue more consistent risk management is part of our creed of “modern investment management”.

[1] Datasets are courtesy of Kenneth French and details of calculation methodologies are available on his website.

[2] We define down months as being those months where our all-companies portfolio experienced a loss.