Our modus operandi is to be bottom-up investors, studying companies that we think might make for overlooked bargains. This, however, doesn’t entirely free us from thinking about the bigger picture both within markets and the world at large. As we zoom out from “micro” to “macro”, we have to make do with abstractions as the complexity of the real world otherwise becomes overwhelming.

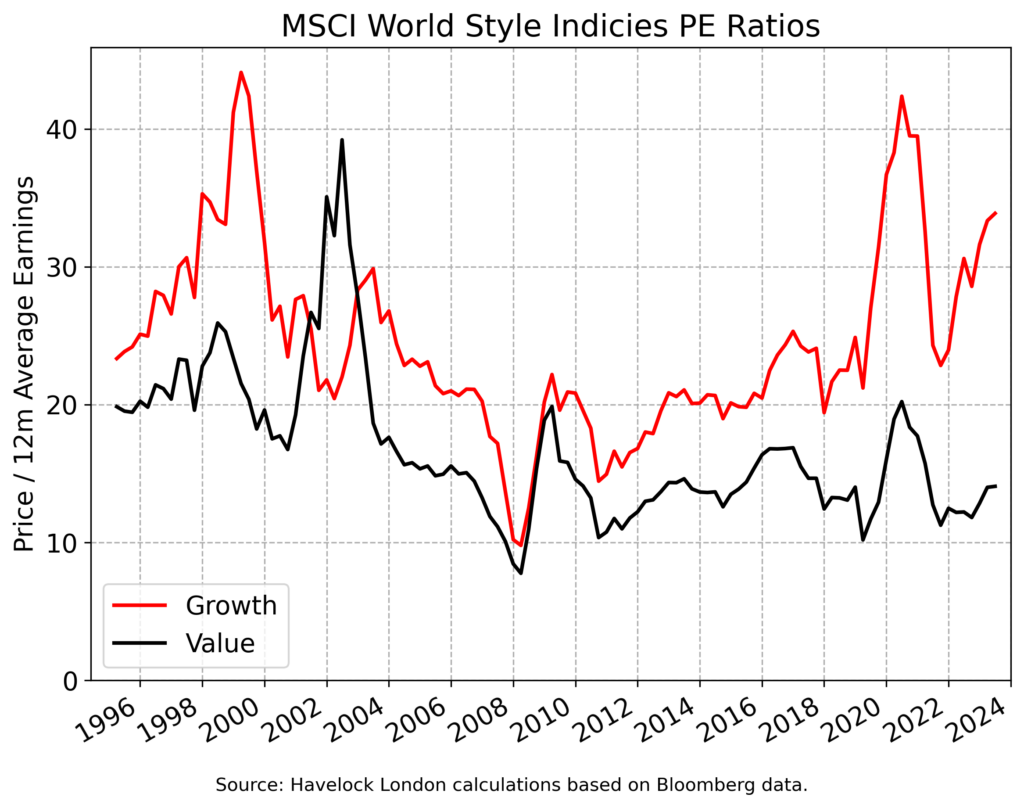

One such abstraction is “value” versus “growth”. Although it seems absurd to categorize 1000s of companies as either displaying one characteristic, or the other, it is a simple and convenient approximation of two different investment approaches. I, like many other value investors, have been quick to highlight the increasing premium that investors have paid to own “growth”. This is shown below by the price earnings ratios of the MSCI World Growth and Value indices.

The chart shows that investors have been willing to pay an increasingly high multiple of earnings for the growth index in the last fifteen years. This “multiple expansion” has created a performance tail wind for growth investors, that has left many companies looking expensive relative to history.

The big question is what does this mean for prospective future returns? Does “growth” face a prolonged period of underperformance versus “value”?

I see three possible explanations for the current high premium being paid for growth, each of which would lead to a different conclusion about the future:

- There is a rational reason why investors are paying such a high premium.

- Investors aren’t paying a high premium, because price earnings ratios misstate it.

- The high premium is irrational.

Prior to 2022 “conventional wisdom” suggested the elevated premium for growth stocks was rational, because interest rates were so low. For the benefit of readers who live in a cave, the argument was that earnings in the distant future had become more valuable in terms of “today’s money”, implying a “bird in the hand” was worth “one in the bush” and not “two”.

Given today’s higher rates, the interest rate justification for this premium isn’t credible. Could it be that the premium has increased this year because markets are “discounting” interest rates falling back to previous levels? Given that the growth index price earnings ratio is higher than at most times when rates actually were close to zero, this argument seems like a stretch.

There have been, and will be, other rationalisations for the premium. For example, that Generative AI will unleash a new wave of earnings growth for a select group of companies. I haven’t seen an explanation that I find credible, but it doesn’t mean that one doesn’t exist.

The second possibility is that an analysis based on price earnings ratios is misstating the premium. This argument holds more sway with me, as “earnings” are a complex and somewhat artificial construct. For example, many highly valued companies derive their earnings from intangible assets, and it can be argued[1] that accounting rules tend to understate profitability in this instance. Similarly, a recent paper[2] used a measure termed “economic profits” to show a small group of large companies making an outsized contribution, but did not venture onto what valuation investors should pay to own them.

Given that the growth index is also at an historically high premium based on price-to-cashflow and enterprise-value-to-EBITDA ratios, I am sceptical of “new paradigm” type explanations. I do however accept that price-earnings ratios, or the style indices themselves, might be misrepresenting the size of the premium that investors are paying for growth companies.

The third explanation is that the high premium is irrational, and that it represents a “bubble”. Clearly, we all rationalise things differently, and so perhaps what is irrational to me isn’t to others?

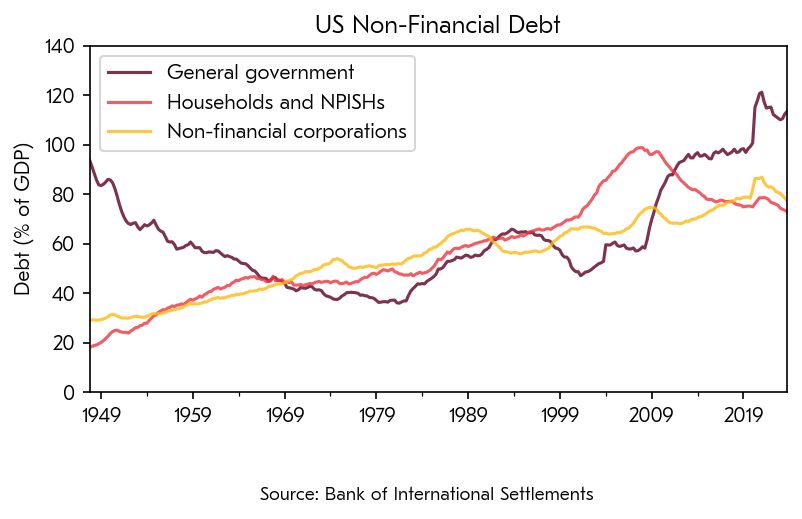

My preferred explanation is that the high premium is the product of governments and central banks underwriting risk in markets. Again, for the benefit of cave dwelling readers, the 2008 crisis was handled by “pumping” liquidity into the financial system, with central banks using newly created money to purchase financial assets. The majority of these assets were government bonds, and so the net effect was both to raise asset prices and put money into government coffers. The same approach was repeated during the COVID crisis. The chart below shows US non-financial debts since 1948, broken down between government, households and companies. The chart for the UK looks very similar, but I focus on the US given its dominance in financial markets.

This chart tells multiple stories. It shows the rapid build-up of household debt prior to the 2008 financial crisis, and how the subsequent deleveraging came at the expense of increased government borrowing. It also shows how the shortfall in economic activity during the COVID crisis was funded by a second large increase in government debt.

I believe that the net effect is that most investors have rationalised paying a large premium for the most successful companies, because it appears that central banks will intervene in the event of a large market decline. I do not assume this pattern of “privatised gains” and “socialised losses” must continue, but I can see why others would.

The previous chart also shows how all three categories of borrower have become increasingly indebted over the long term, such that total debt levels in the economy are at a post-war high. I believe that this lies behind many of the political challenges that we currently see, but that is a story for another day!

Economist, Hyman Minsky, theorised that long periods of prosperity and investment gains encourage diminished risk perception and a build-up of debt, that will ultimately end with a “Minsky Moment” collapse in asset prices. The build-up of debt in the world’s major economies is without doubt, and I think that the high premium investors are willing to pay to own growth companies is one of many pieces of evidence that suggest a diminished perception of risk.

The different interpretations of the high premium currently being paid for “growth” would lead to different conclusions about the future. If the premium is rational, or non-existent, then there is no reason for concern. If on the other hand it is irrational, investors in the most expensive companies will likely experience future returns are at best disappointing and at worst stomach-churningly awful.

It would be bold to say that you believe any one of these explanations with complete certainty. I prefer to think in terms of probabilities, and I put a higher likelihood on the premium being irrational, but accept that it is also possible that one of the first two explanations is correct. Only if you are very confident that the high premium is justified, should you be “all in” on growth.

Many investors will draw the conclusion that they wish to guard against the risk of a fall in asset prices by owning the highest quality assets, but this ignores the price paid to purchase them. This approach didn’t work in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when investors in blue chip “Nifty Fifty” companies were subject to a subsequent decade of disappointing returns[3].

Returning to where I started, “value” and “growth” are crude abstractions of a complex reality. The high price earnings multiple for the MSCI World Growth index is driven by individual companies, like Nvidia, each of which will have their own narrative. In the same way that not all “growth” stocks will be overvalued, not all “value” stocks are sub-par duds.

I think that it is the combination of the quality of what you own, and the price you pay, that will best guard against loss of capital. This is the approach that we use, and I believe why we were able to sidestep the large falls in asset prices during 2022.

I do not know what will happen next, but the amount of debt in the world’s major economies puts us in unchartered territory. For this reason, I think it is dangerous to assume that the “status quo” in markets must continue. My best guess is that central banks and governments will sooner, or later, pull back from underwriting the risk of investing, which will place a renewed importance on valuations.

Matthew Beddall

CEO and Fund Manager, Havelock London Ltd

[1] https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_intangiblesandearnings_us.pdf

[2] https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_stockmarketconcentration.pdf